In the world of prediction markets, clear rules and definitions are essential to ensure fair outcomes.

However, Polymarket’s ongoing resolution issue regarding the market titled, “Will Israel invade Lebanon in September?” exposes how ambiguous language and complex geopolitical events can create significant challenges.

Despite the market hitting its deadline on Sept. 30 at 11:59 p.m. ET, and currently being under dispute, bettors show no sign of shying away from the ambiguity that Polymarket finds itself in. Rather, they continue to place bets, capitalizing on the uncertainty.

On the night of Sept. 30, the market sat at $1.7 million; now, it has surged to $4.1 million, reflecting the massive engagement despite the ongoing conundrum.

The market context

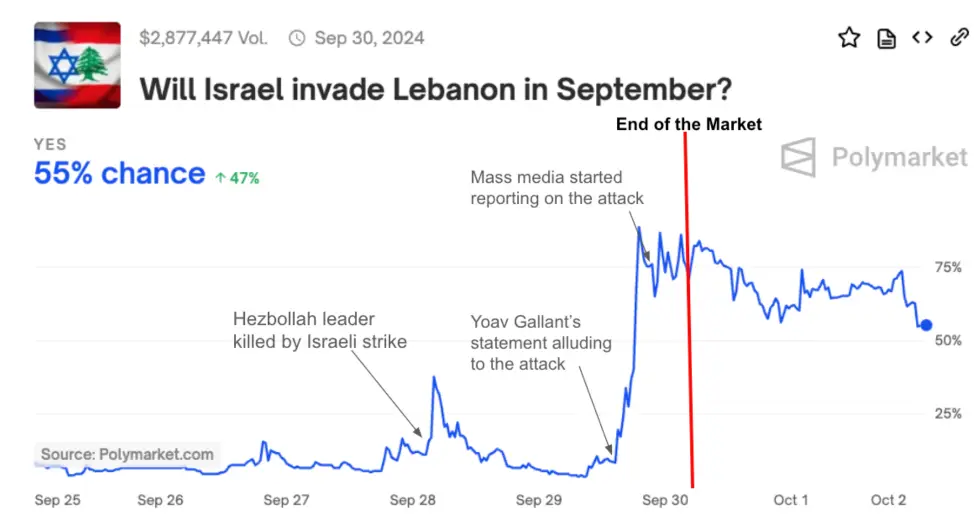

On the morning of Sept. 30, “Yes” shares in the market were priced at only $0.08, suggesting that most participants did not expect an Israeli invasion of Lebanon.

However, by 11 a.m. ET, after a statement from Yoav Gallant, Israel’s Minister of Defense, alluding to an upcoming escalation against Hezbollah, the price jumped to $0.89.

The statement hinted escalation and an imminent invasion, saying “the next phase in the war against Hezbollah.” Traders took note.

במפגש עם ראשי המועצות בפורום קו העימות הדגשתי - השלב הבא במלחמה נגד חיזבאללה יתחיל בקרוב ויהווה גורם משמעותי עבור השגת מטרת המלחמה - החזרת תושבי הצפון לבתיהם. pic.twitter.com/5UsmcPrmT7

— יואב גלנט - Yoav Gallant (@yoavgallant) September 30, 2024

As the day progressed, major media outlets across the globe began labeling Israel’s actions as an “invasion” or “incursion,” pushing Yes shares to $0.87.

For most traders, the market seemed to reflect the growing consensus in the media. However, the ambiguity in Polymarket’s rule soon surfaced, and the market’s price stagnated.

Despite the overwhelming use of the term “invasion” in the media, a number of traders remained skeptical, pointing out that Polymarket’s resolution criteria were far more nuanced.

The ambiguity of definitions

The crux of the dispute lies in the market’s resolution criteria, which state that “This market will resolve to “Yes” if Israel commences a military offensive intended to establish control over any portion of Lebanon.”

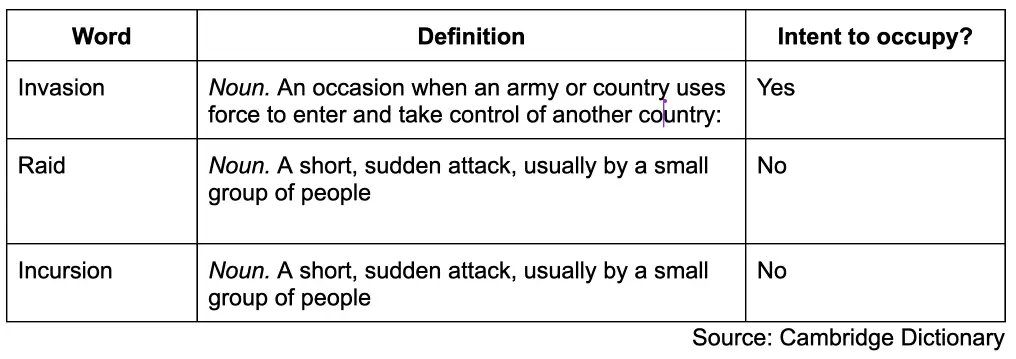

This wording leaves much room for interpretation, especially when differentiating between military terms such as “invasion,” “raid,” and “incursion.” While the media may use these terms interchangeably, the nuances between them have real consequences in a prediction market.

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, an invasion is defined as “an occasion when an army or country uses force to enter and take control of another country.” This definition implies a long-term or sustained occupation—something clearly different from a “raid” or “incursion,” which the same dictionary defines as short, sudden attacks with no intent to occupy.

Israel’s official stance added to the confusion. The Israel Defense Forces described their actions as “limited, localized, and targeted ground raids.” Two Israeli officials reiterated this position, asserting that the military operations did not aim to establish control over Southern Lebanon, reported by Axios.

In accordance with the decision of the political echelon, a few hours ago, the IDF began limited, localized, and targeted ground raids based on precise intelligence against Hezbollah terrorist targets and infrastructure in southern Lebanon. These targets are located in villages…

— Israel Defense Forces (@IDF) September 30, 2024

This directly conflicts with the criteria for a “Yes” resolution on Polymarket, where the intent to occupy appears to be a key element.

The market’s dilemma: Who to trust?

The Polymarket rule further complicates matters by stipulating that the resolution will be based on “official confirmation by Lebanon, Israel, the United Nations, or any permanent member of the UN Security Council,” or alternatively, through a “consensus of credible reporting.”

However, credible reporting itself often reflects the ambiguity of the situation, with terms like “invasion,” “raid,” and “incursion” used inconsistently across outlets. This raises a fundamental issue with prediction markets on geopolitical events: how do you quantify an action that is subject to interpretation?

Unlike a market based on numbers, such as predicting the Federal Reserve’s rate cuts, geopolitical markets rely heavily on how events are framed. In this case, Israel’s official terminology—ground raids without occupation—provides one perspective, while the media’s broader labeling of Israel’s actions as an “invasion” offers another.

With no objective measurement for intent, traders are left grappling with conflicting interpretations.

Traders’ frustration

Polymarket’s struggle to resolve this particular market highlights a larger challenge in event-based prediction markets. These markets are, by nature, harder to quantify than their numerical counterparts. When the rules depend on subjective interpretations of complex events, such as military actions, traders and market organizers alike are forced into a gray area where outcomes are far from certain.

In this case, even if Israel continues its military activities in Lebanon, its official statements, claiming no intent to occupy, could still prevent the market from resolving to “Yes.” This discrepancy illustrates how difficult it can be to prove intent in an event market, especially when one party—the one conducting the action—controls the narrative.